Kids aren't simply small adults. This guidance applies in the context of many medical conditions, and it's especially true in evaluating a child for a potential arrhythmia. As with adults, a child's normal heart rate depends on a number of variables, and age is one of the primary factors. A normal heart rate for a 12-year-old is around 55–85 beats per minute, compared to an infant's rate of roughly 100–150 beats per minute.1

While many arrhythmias in pediatrics are harmless, it's vital to distinguish between the different types to ensure that any potentially harmful and treatable ones are caught early.2 In cases of suspected arrhythmias in children, conducting diagnostic tests to establish a baseline can be useful in identifying and diagnosing heart issues that require monitoring.

What To Know about the Most Common Arrhythmias in Children

An irregular heartbeat in children is not usually concerning for cardiologists or pediatricians, but it can be scary for parents. An arrhythmia can be caused by a congenital heart defect or cardiomyopathy, or it could be from an infection, fever, medications, exercise, or strong emotions.

An arrhythmia's symptoms can mimic those of other health conditions. Besides heart palpitations or noticeable pauses between heartbeats, symptoms may include:

- Weakness and fatigue

- Dizziness and fainting

- Low blood pressure

- Chest pain

- Shortness of breath

- Sweating

- Irritability

- Not eating well

Conversely, a child may present with no evident symptoms at all. Here are some arrhythmias to look for in pediatric patients.

Complete Heart Block

A complete heart block occurs when the electrical signal between the upper and lower chambers is blocked, which often causes the heart rate to slow and the patient to experience fainting episodes. A complete heart block can occur after heart surgery or due to a heart muscle injury, or it could stem from heart disease. Heart block can also be congenital and present in utero. About 1 in 15,000 to 20,000 babies are born with congenital heart block.3

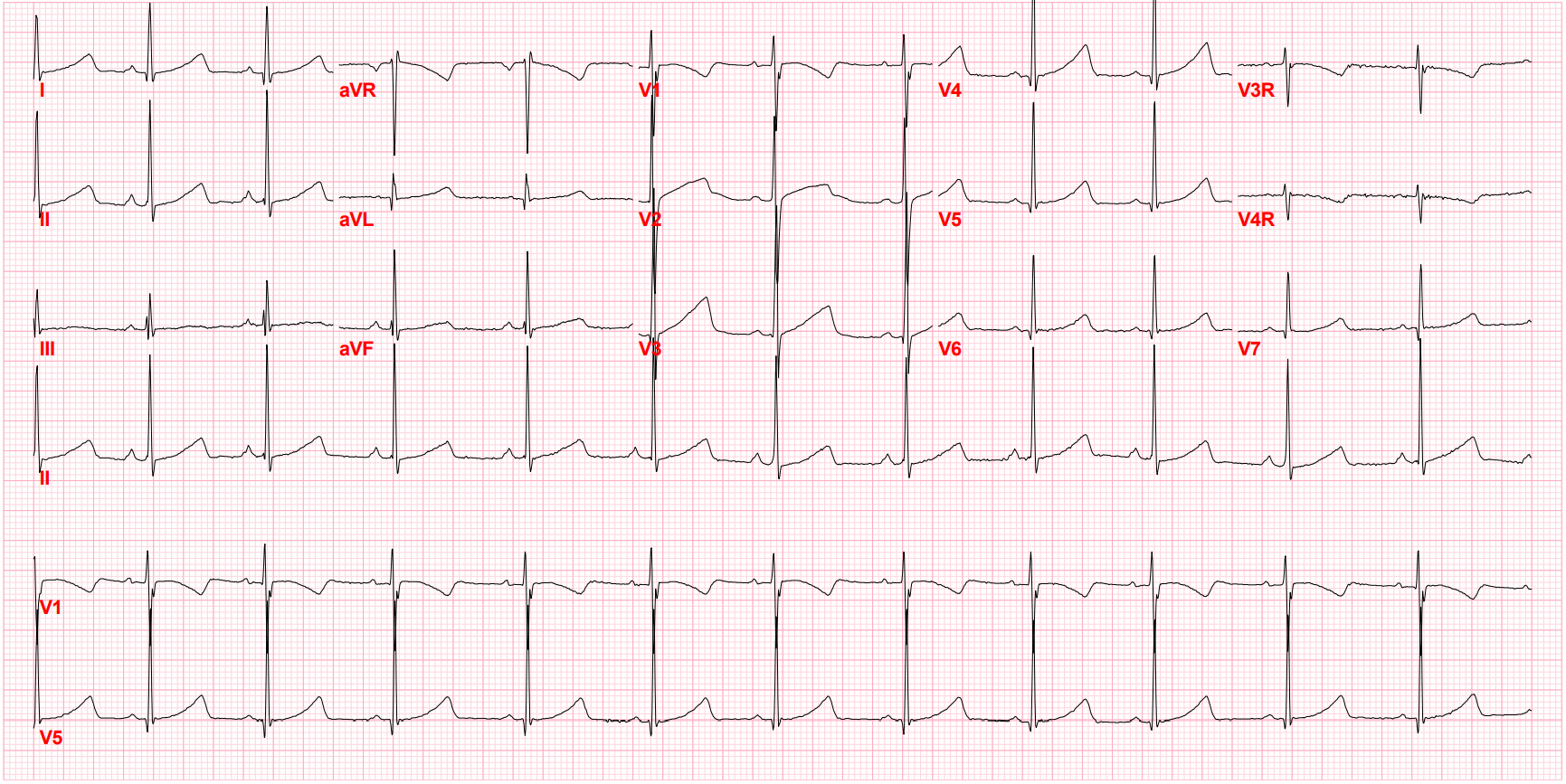

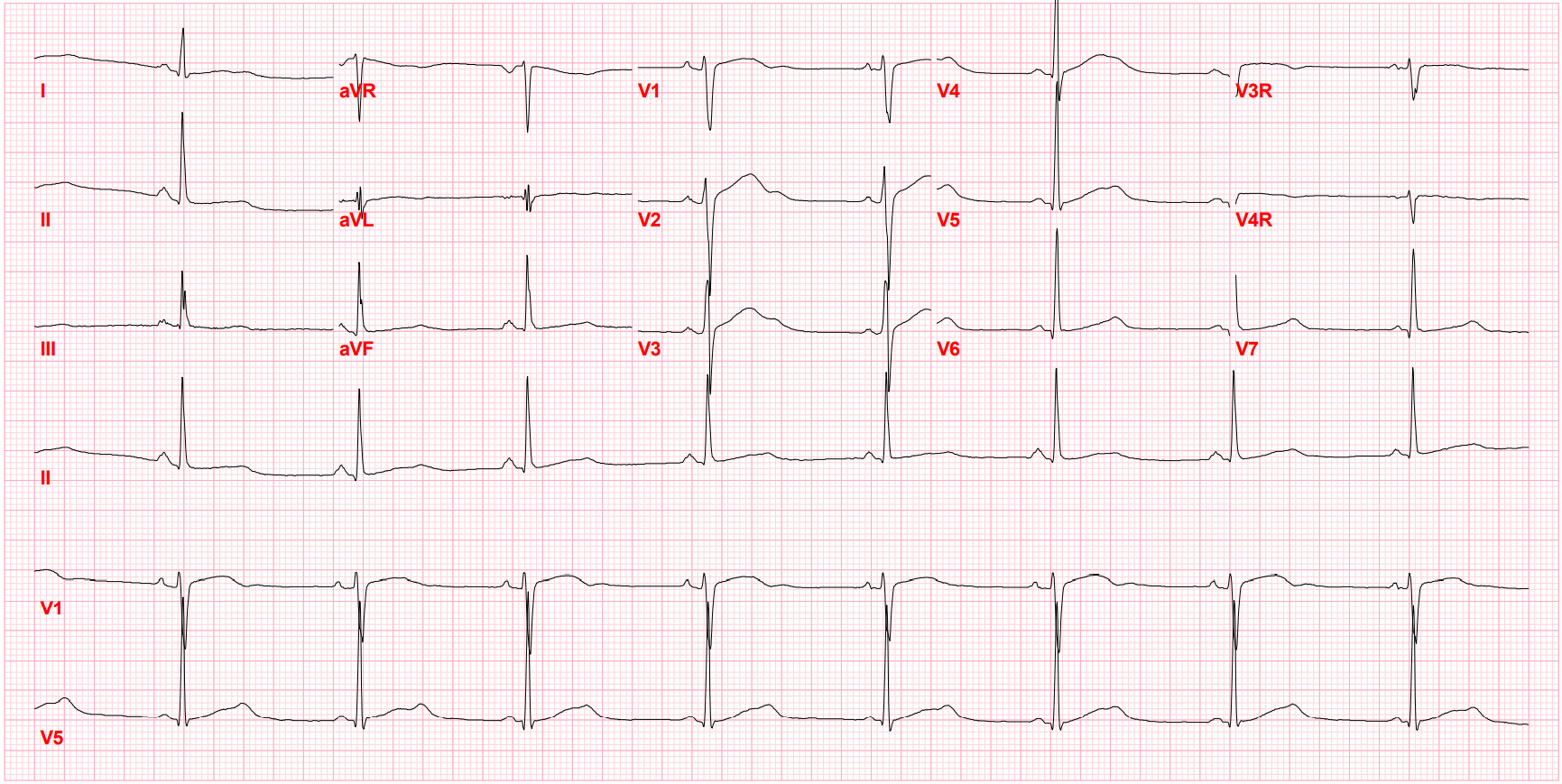

Long QT Syndrome

Long QT syndrome is an inherited condition that can affect children and young adults, but it may not cause symptoms. Patients who do have symptoms may experience fainting, irregular heart rates or rhythms, fluttering in the chest, or even cardiac arrest. The symptoms of long QT syndrome may be triggered by physical exercise, a startling noise, or intense emotions or pain. Long QT syndrome causes 3,000-4,000 sudden deaths in children and young adults annually in the U.S. The condition can be inherited, as 50% of children with Long QT syndrome also have a parent or sibling with it. 4

Prolonged QT, 9 Year old female (QTc 502 Bazetts)

Prolonged QT, 15 year old male (QTc 519 Bazetts)

Premature Atrial Contractions (PAC) and Premature Ventricular Contraction (PVC)

These abnormal heartbeats begin in the upper atria or lower ventricles, respectively.5 They are considered harmless and commonly occur in children and teenagers. While they're usually of uncertain etiology, they can sometimes be caused by a heart injury or disease, but they are rarely indicative of an abnormal heart.

Sick Sinus Syndrome

Sick sinus syndrome occurs when the child's sinus node does not work properly, resulting in slowed or rapid heart rates.6 There may be no symptoms, or the child might faint or experience dizziness or fatigue. Sick sinus syndrome can occur in children who have undergone open-heart surgery.

Sinus Tachycardia

Sinus tachycardia is a rapid heart rate that is considered normal. Children may experience it when they have a fever, or during exercise or episodes of excitement. Occasionally, it is caused by conditions like anemia or increased thyroid activity. In these cases, treatment of the underlying issue can resolve the tachycardia. 7

Supraventricular Tachycardia (SVT)

This condition, along with paroxysmal atrial tachycardia (PAT) and paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia (PSVT), is most common in the pediatric setting and is caused by an abnormal electrical circuit in the heart. SVT is usually diagnosed in older children and can cause heart palpitations, dizziness, chest discomfort, upset stomach, weakness, and lightheadedness. The heart can beat rapidly at 180-280 beats per minute in children, and up to 300 beats per minute in infants. SVT occurs in up to 1 in 2,500 children.8 Note that in children with SVT, there are often no P waves evident.

Wolff-Parkinson-White Syndrome (WPW)

With WPW, the electrical pathways between upper and lower heart chambers malfunction, and the signals reach the ventricles too early. Those signals quickly return to the atria, sometimes causing rapid heart rates. About 8 in 10,000 children have WPW.9 It is a subset of SVT and the most common type of SVT in children.8

Stay on top of cardiology trends and best practices by browsing our Diagnostic ECG Clinical Insights Center.

Diagnosing and Evaluating Arrhythmias in Pediatrics

Reading an ECG is different for children and adults, however, as the heart is not yet mature during the child's growth process. As the child enters adolescence, the ECG patterns adhere more closely, but not completely, to patterns seen in adult ECGs.

While a 12-lead ECG system is standard in primary care settings, many pediatric cardiology clinics opt for the more sensitive 15-lead setting, which adds V3R, V4R, and V7 leads.

If the ECG is not definitive, the cardiologist might supplement it with another diagnostic test. This can include using a Holter monitor for 24-48 hours to record the heart rhythm during usual activities, or performing an electrophysiologic study to determine the electrical signal type causing the issue. A tilt table test may be done to assess the heart rate and blood pressure while the child is in different positions, if the child frequently faints.

Determining whether a pediatric patient has an arrhythmia—and if so, which type—is the first step toward reassuring parents and putting the patient on the path toward necessary treatment. Some pediatric cardiology patients may need long-term follow-up, and making their first cardiology experience a positive and illuminating one can help them achieve better lifelong heart health.

References

- Weinberger SM. Arrhythmia (Abnormal Heartbeat). Kids Health. https://kidshealth.org/en/parents/arrhythmias.html. Accessed June 13, 2022.

- Arrhythmias in Children. Cleveland Clinic. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/14788-arrhythmias-in-children. Accessed June 13, 2022.

- Baruteau AE, Pass RH, Thambo JB, et al. Congenital and childhood atrioventricular blocks: pathophysiology and contemporary management. European Journal of Pediatrics. 2016; 175(9): 1235–1248. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5005411/.

- Long QT Syndrome. Boston Children's Hospital. https://www.childrenshospital.org/conditions/long-qt-syndrome. Accessed June 13, 2022.

- Heaton J, Yandrapalli S. Premature atrial contractions. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559204/. January 2022. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing 2022.

- Sick sinus syndrome. Medline Plus. https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/000161.htm. Accessed June 13, 2022.

- Henning A, Krawiec C. Sinus Tachycardia. January 2022. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK553128/.

- CS Mott Children's Hospital. Supraventricular tachycardia. University of Michigan Health. https://www.mottchildren.org/conditions-treatments/ped-heart/conditions/supraventricular-tachycardia. Accessed June 13, 2022.

- Chubb H, Ceresnak SR. A proposed approach to the asymptomatic pediatric patient with Wolff-Parkinson-White. HeartRhythm Case Reports. January 2020; 6:1: 2–7. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6962761/