In 2015, former U.S. President Jimmy Carter was diagnosed at age 90 with metastatic melanoma that had spread to his liver and brain. Thinking he might have only weeks to live, he was enrolled in a clinical trial for an investigational immunotherapy called pembrolizumab (Keytruda). After being treated with this immunotherapy and radiation therapy, he announced, at age 91, that he was cancer-free. Carter’s experience shined a spotlight on the potential for immunotherapy in cancer treatment.

What Is Immunotherapy?

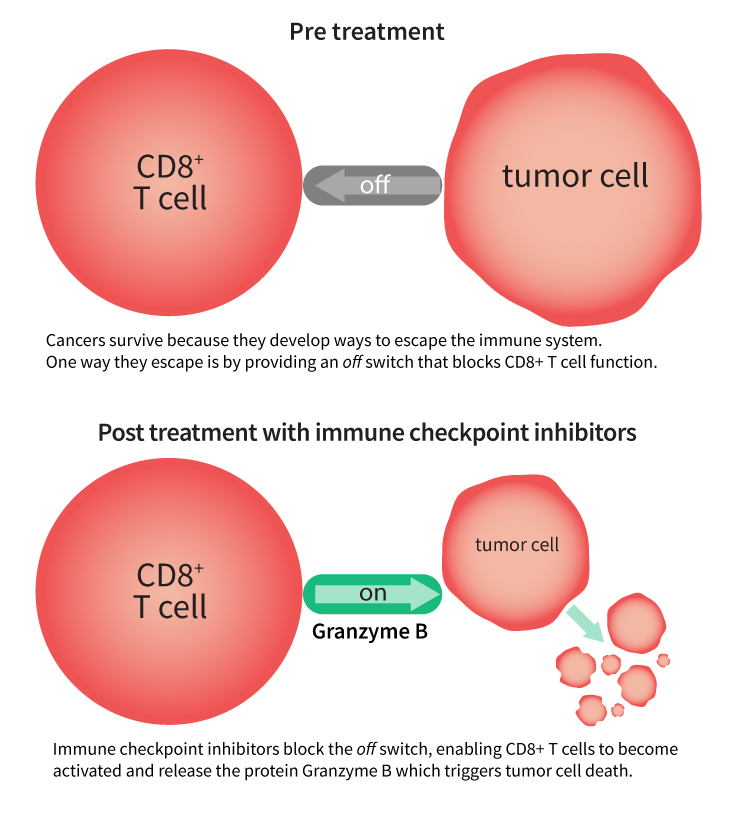

Immunotherapy uses a person’s own immune system to fight cancer. The immune system can target cancer on its own, but in some people cancers develop mechanisms that include “switching off” immune cells in tumors, says Dr. Elaine Long, GE HealthCare’s immuno-oncology global scientific lead. “Some classes of immunotherapies can block the off switch, allowing an important type of immune cells called CD8+ T cells to become activated and secrete an effector enzyme called granzyme B, which is central to killing cancer cells. Understanding whether these CD8+ immune cells are activated, and producing granzyme B, could reduce the time patients spend on ineffective therapies and also enable physicians to switch patients who are non-responders to alternative treatments sooner,” she explains.

This GE HealthCare illustration demonstrates immune checkpoint inhibitor mechanism of action. Credit: GE HealthCare. Top: Artist rendering of a T cell attacking a cancer cell. Credit: Roger Harris/Science Photo Library via Getty Images.

Immunotherapy has revolutionized the way we think about cancer treatment in recent years, offering hope to people with certain types of cancer where there once was little. Successes have led to a massive increase in drug development, with therapies in the immuno-oncology pipeline growing 233% between 2017 and 2020, according to the Cancer Research Institute.

Currently approved immunotherapies can be incredibly effective in some people, like former President Carter. Researchers have found, however, that 20% to 40% of patients with metastatic melanoma respond to “checkpoint inhibitors,” which are the main class of approved cancer immunotherapy drugs. Determining whether a patient is responding can take considerable time, says Long.

Today, for example, she says that if a person is diagnosed with advanced melanoma, a healthcare provider will biopsy their tumor to test for expression of a biomarker which is an indicator that they are more likely to benefit from checkpoint inhibitors. However, that biomarker only gives information about the tissue biopsied rather than a whole-body view. If the biomarker is present in the tumor sample, the patient will begin treatment and the clinician will continue to monitor the tumor size over time, using a pre-treatment CT scan as a comparison. “It takes months before their doctor has an idea about whether they’re responding to their therapy,” she says.

There are other challenges too, alongside lack of response, including potentially avoidable adverse effects and the high cost of therapies. GE HealthCare is addressing these challenges by developing diagnostics that aim to help identify a patient’s likelihood to respond to immunotherapies before starting cancer treatment, as well as enabling faster and earlier monitoring of a patient’s response once they start treatment. This could help avoid unnecessary treatment for those less likely to respond, or those not responding, who could be offered alternative treatment options earlier.

A recent study called TracerX, published in a series of back-to-back articles in Nature and Nature Medicine, has provided in-depth information about how cancers evolve and spread over time (see Karasaki, Al-Sawaf, Abbosh, Frankell, and Al Bakir). As tumors develop, they can become more aggressive and better at evading the immune system. By using precision diagnostics, clinicians can better understand this process and the status of individual patient tumors, so they can more precisely select the most appropriate treatment combinations.

“Knowing very early on whether a patient is responding, rather than waiting months, can make a big difference,” says Long. “These cancers are continually evolving. The earlier you can address the disease and treat it, the better, because the more advanced the disease gets, the more challenging it is to treat.”

Innovating in Immunotherapy Diagnostics

In an effort to better predict and monitor early response to cancer immunotherapies, the immuno-oncology team at GE HealthCare is conducting a Phase I clinical trial, which began in March 2023, studying the safety and tolerability of the 18F-labeled radiopharmaceutical in patients with solid tumor malignancies. Using an 18F-CD8 positron emission tomography (PET) imaging investigational agent, researchers are hoping to understand whether patients have CD8+ T cells in their tumors and will therefore be more likely to respond to immune checkpoint inhibitors.

Currently, using RECIST (response evaluation criteria in solid tumors), doctors and patients wait months to find out if treatment is working. With this investigational diagnostic, Long says, “it may be possible to see whether you’re getting a response within days.”

Long believes that diagnostics such as these could be game-changing in cancer research and treatment. This kind of PET imaging could also, she says, potentially enable pharmaceutical companies and researchers to select the most appropriate patients for clinical trials and measure how a drug is working, helping bring new immunotherapies to market.

Derk Jan de Groot, MD, PhD, a medical oncologist at the University Medical Center Groningen, in the Netherlands, says, “We’ve seen significant innovations in immunotherapies over the last few years. To more effectively select patients for immunotherapy, we need better predictive tools. The research underway with CD8 holds much promise and could potentially open the door on speeding up advances in precision care, to further improve patient outcomes.”

For years, the healthcare community and patients alike have been abuzz about the possibilities of precision care. And for good reason. A decade ago, advanced melanoma was a death sentence: Just 5% of people with advanced melanoma survived five years. Today, Long says, through the use of immunotherapy drugs along with other cancer treatments, those odds have changed considerably, resulting in a 52% five-year survival rate in people with advanced melanoma.

Now, Long believes, we’re entering a new phase of personalized diagnostics that could result in a more definitive and complete understanding of how an individual patient’s immune system — and cancer — responds to therapy.

“There are more than 5,000 immunotherapy drugs in development,” she points out. “Using the power of diagnostics to better understand tumor and immune status at a whole-body level could hold the key to more confidently identifying which treatment, or treatment combinations, are likely to be most effective for each individual patient. Just think about all the different cancer types — potentially, there are immunotherapies that may be effective for each of them. But to unlock that potential, we must understand which patients will benefit from which treatments.”