Despite a Ph.D. in nuclear engineering and two research stints at Yale University, Marialisa Stagliano searched without luck for nearly a year to find a job in engineering in her native Italy. Potential employers insisted on steering her into sales and marketing, not the hands-on technical work that was her specialty and passion.

It was always a sales position, because I’m a woman,” she says. One interviewer even told her: “You are pretty, so you can fill our sales marketing position.”

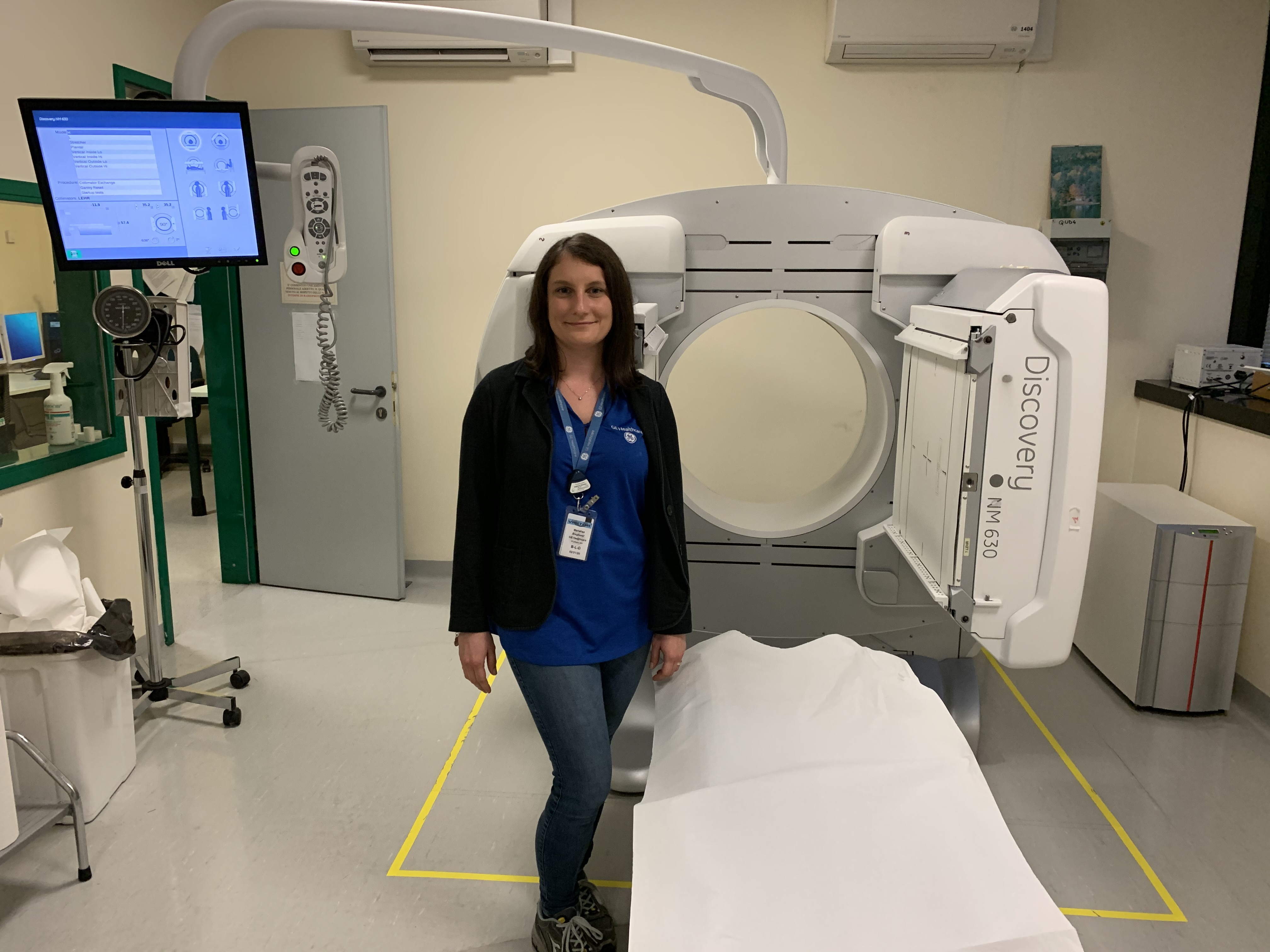

Then Stagliano read about GE’s “Balance the Equation” corporate initiative to boost the numbers of women in technical positions and landed the right job at GE Healthcare as a field engineer, installing, maintaining and repairing ventilators, monitors and nuclear medical imaging machines.

The molecular imaging machines, known as gamma cameras, are used in cancer diagnosis to track tiny amounts of radioactive tracer that are injected into a patient to detect tumors and other conditions.

Stagliano travels to approximately 20 hospitals and even more clinics in the Tuscany region to work on GE Healthcare’s imaging machines and gamma cameras, as well as ventilators, anesthesia machines and patient-monitoring solutions that measure pressure, oxygen levels, cardiac rates and the like. [1][2][3]

When Stagliano arrives at hospitals to work on equipment, some people express surprise that she is a woman. She says she has hardly ever met another woman in a job like hers. Clad in protective gear, she is often mistaken for a nurse, and she has been questioned as to why she is doing a “man’s” job.

Only one in three scientists or engineers in Italy is a woman, according to Eurostat, the European Union’s statistical office.[4] She was one of the few women to graduate from her doctoral program in 2018 at the University of Pisa, where, a couple of years before, a professor had flatly told her she would never become an engineer because of her gender.

“Now I laugh about it, because I found a company and colleagues who treat me exactly the same,” says Stagliano, now 31. “There is no difference at all. A job doesn’t have a gender … is not male or female.”

GE has nearly 174,000 employees in more than 170 countries.[5] Globally, 32.1% of GE Healthcare’s professional staff are women.[6] Like all the GE businesses, it has a chief diversity officer to keep it accountable to its diversity initiatives.

“In Italy, it’s not so common that a female wants to do what I do,” Stagliano says. “Maybe it’s a cultural thing.” She credits her family with encouraging her technical side, recalling that when she played with dolls as a child, she didn’t just dress them but also built them furniture.

Today she makes sure GE Healthcare’s equipment is installed properly and running smoothly. She uses highly sophisticated tools to analyze problems, she says, but her work is hands-on. Once a problem is identified, usually “you take the screwdriver and you fix it.”

One advantage of working at GE Healthcare is that field engineers and other technicians share information and advice nationally and globally, and she is always learning from people around the world. She lives near Florence, in a town called Empoli, with her husband.

Stagliano started at GE Healthcare in 2018 and completed her doctorate at the beginning of 2019. She previously spent three months as an undergraduate and three months as a graduate student working on a research project at Yale University, in New Haven, Connecticut. As an alumna, she returns to the University of Pisa to represent GE Healthcare and talk to students, who she says pepper her with questions about her career and her daily job.

“Maybe somebody sees my experience and says, ‘Well, if she can do that, I can do that.’ In fact, one of those students, a woman, recently contacted her in hopes of landing an internship at GE Healthcare for a master’s thesis in field engineering.

Her advice to students: Be positive, be brave and surround yourself with people who believe in you. “GE? They believe in me,” she says. “I was very lucky.”

But, she adds, the best part of her job is knowing its impact on those who need her help. She recalls a time when she and a colleague were repairing a gamma camera and there was a knock on the door. A young girl no more than eight years old, a cancer patient, was there to see the machine that doctors planned to use to scan her the next day.

“That child was very sick, so my colleague and I worked until late in the evening to fix the machine,” she says. “The day after, we called the department and they said yes, everything was fine. The machine worked perfectly, and it went well. That day, I was so happy. I was so proud of my job.”

These days, relieved hospital and clinic staff welcome her help servicing much-needed ventilators as they battle COVID-19. The pandemic has hit hard in Italy, killing more than 95,000 people.[7]

“I remember a chief of nurses, during the first months of the pandemic, came up to me and asked when will the machine be ready for a patient again,” she says. “She came back to me [later that day] and said, ‘OK, today you may have saved a life.’”

[1] Johns Hopkins Medicine, Nuclear Medicine

https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/treatment-tests-and-therapies/nuclear-medicine

[2] GE Healthcare Ventilators

https://www.gehealthcare.com/products/ventilators

[3] GE Healthcare Patient Monitoring

https://www.gehealthcare.com/products/patient-monitoring/patient-monitors

[4] Eurostat, Women in Science and Technology

https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/-/EDN-20200210-2

[5] GE 2020 Diversity Annual Report

https://www.ge.com/sites/default/files/DiversityReport_02122021.pdf

[6] GE 2020 Diversity Annual Report

https://www.ge.com/sites/default/files/DiversityReport_02122021.pdf

[7[ World Health Organization, Italy, COVID Statistics

https://www.who.int/countries/ita