He spent a career inventing lifesaving equipment. It took everything his family, his GE colleagues and the healthcare community had to save him.

The day that would have been Bob Senzig’s last is still a haze and probably always will be. He remembers his doctor at the hospital in the resort town of Los Cabos, Mexico, arguing on the phone with the crew of a medical evacuation jet coming to ferry him back to the U.S. He knew that, if he wanted to live, he would have to get on the plane. To get on the plane, he was told, he would have to be intubated, which would require him to be unconscious. Make your phone calls and quickly, his doctor told him. He recalls speaking to his mother and son and then leaving a voicemail for his wife. Everything was a fog. He couldn’t concentrate. He couldn’t breathe. Then the doctor put him under.

Some 43 million Americans have been infected with COVID-19 since the pandemic struck and over 692,000 of them have died as of late September. As vaccines have rolled out and treatment at hospitals has improved, it’s easy to forget how capricious the coronavirus can be. How one person can suffer a headache while their spouse or parent is left gasping for breath. For those experiencing severe symptoms, surviving the disease can require an almost absurd combination of resources and resolve from both healthcare providers and patients.

Pulling through

Senzig’s ordeal, which began in late fall 2020, serves as a reminder. The 66-year-old retiree would wake up a month and a half later in Phoenix with only the vaguest sense of what he, his family, friends and the team caring for him had just been through to keep him alive. It would take months of care before Senzig, who had lost enough muscle to make lifting an iPad impossible, could walk, talk and smile again. Today he’s well enough to resume ballroom dancing and not without a sense of humor about his ordeal — he titled a log he kept “Bob’s Covid Adventure” — but about other things he’s deadly serious. COVID is real. Vaccines can help reduce the severity of COVID symptoms. Doctors and nurses are performing superhuman feats to save Americans from death.

“Some people still feel this isn't a real thing,” he says.

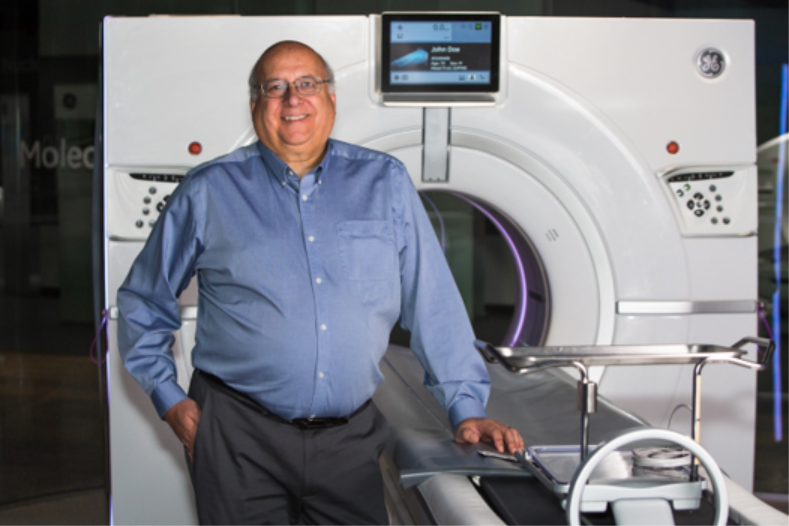

Senzig knows how complicated saving a life can be. Up until his retirement, he served as GE Healthcare’s chief engineer for CT scanners. Over a career spanning 36 years, there hasn’t been an advance in computed tomography that Senzig hasn’t touched in some way. Work he did years ago continues to produce breakthroughs for healthcare today, like the acquisition of a Swedish startup, Prismatic Sensors, that he helped GE complete right around the time he left on for his ill-fated vacation. Prismatic specializes in producing Deep Silicon photon-counting sensors. Photon counting CT technology has the promise to further expand the clinical capabilities of traditional CT, including the visualization of minute details of organ structures, improved tissue characterization, more accurate material density measurement (or quantification) and lower radiation dose.[1]

Career innovator

Raised in Racine, Wisconsin, Senzig helped out on his grandparents’ dairy farm as a kid and studied mechanical engineering in Milwaukee. He joined GE in 1982 and got to work designing cutting-edge CT machines. At the time CT was slow, making it hard to scan a patient’s body, and images were stored on 9-track magnetic tapes or 8-inch floppy disks. Senzig helped lead many of the advances that went on to make CT scanning fast and ubiquitous and rose through the ranks to be named chief engineer in 2001.

In that role Senzig focused on mentoring scientists and engineers and helped build teams around the world that would broaden GE’s CT expertise. When he retired in 2018, Bob was an inventor on 46 U.S. patents and had authored numerous scientific publications. He was collaborating with a former GE colleague on 3D-printed personal protective equipment for healthcare workers when the desire to escape the isolation of the pandemic led him to make a bad decision.

Turning point

A friend called and asked if Senzig and his wife would join in a brief trip to Mexico in November 2020 before the friend underwent major surgery. He agreed. Senzig says he rationalized taking the risk, putting aside his doubts. He and his wife tested negative for COVID before getting on the plane. But, by the time the pair landed, he was already feeling ill. Soon he had a headache and a cough and was cleaning out the hotel sundry shop for medicine.

Admitted to a local hospital, his blood-oxygen level dropped, and he struggled to breathe. Beset by brain fog that made it difficult to follow even simple instructions, he texted his PPE collaborator and told him he needed to leave Mexico or he would die. Senzig’s doctor in Los Cabos warned him that people who are intubated and fighting severe COVID don’t do well if they leave the hospital. Senzig decided he had to risk it.

“I was very conflicted as to what to do,” Senzig says. “I was terrified.”

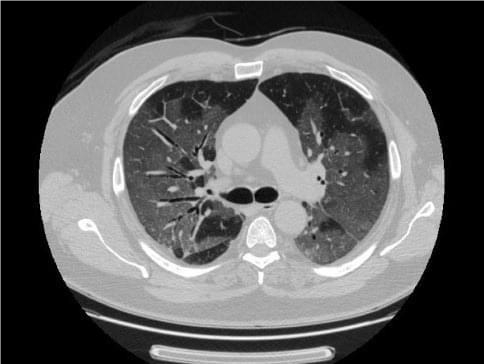

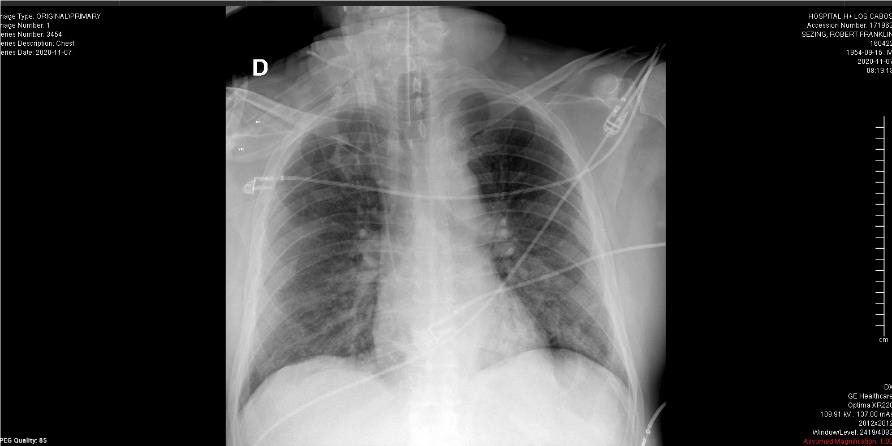

Having spent a lifetime looking at CT scans, Senzig was somewhat cheered to see that the hospital was scanning him on a GE BrightSpeed machine that he helped to design and make affordable. “It was good to see a familiar ‘face’ when I was so sick,” he says. During this COVID 19 pandemic, CT scans are sometimes used by trained physicians to help diagnose COVID pneumonia as well as to assess the severity of the disease which is helpful in patient care management.[2] A scan taken shortly before his flight showed his lungs overwhelmed by COVID pneumonia.

Support system

Senzig had left the U.S. on Halloween. He awoke in a hospital bed in mid-December, unable to speak, read or think straight, having lost 65 pounds and breathing through a tracheotomy tube. While Senzig was sedated, his collaborator and former GE colleague had put the $25,000 air ambulance cost on his own credit card and spent days negotiating to get Senzig through customs and into a then-scarce ICU bed in the U.S. Doctors, nurses and ventilator technicians had fought day and night for weeks to save him, and friends and family had stayed in constant contact with the medical team and one another. A site set up to raise funds for Senzig drew donations from more than 200 people from around the world, many of them former GE colleagues.

By mid-December, Senzig was breathing on his own again and a few weeks later he was home, albeit using a walker to get around. He would go through months of physical, voice and occupational therapy as well as a flurry of doctor visits. After he did poorly in a respiratory test, CT scans were used to study the permanent damage COVID did to his lungs. His post-hospitalization scans were done on a Discovery CT750 HD that he helped develop. But he’s alive, vaccinated and back at his favorite hobby, ballroom dancing. And he’s grateful to the staff who kept him alive, to his friends and family who watched over his condition while he was in the hospital and to the GE colleagues who supported him throughout. He wonders if the ventilator that kept him alive was one that GE employee volunteers produced in its production surge early in the pandemic.

Senzig and his friend published their PPE designs online for anyone to use, though with vaccines now widely available, he thinks they’ll only be of use in a future epidemic. He’s also published accounts of his experience on social media to raise awareness of both the dangers of COVID and the doctors and nurses who deal with the damage it does. None of it, he says, feels like enough: “How do I say thank you to the healthcare workers who helped me? The best way to help reduce the pressure on the healthcare system is to follow good hygiene practices and to get vaccinated.”

[1] “GE Healthcare Pioneers Photon Counting CT with Prismatic Sensors Acquisition.” GE.com, Nov. 20, 2020.

[2] “The Usefulness of Chest CT Imaging in Patients With Suspected or Diagnosed COVID-19.” Chest Journal. Aug. 1, 2021.