Mark Frontera always felt that his work mattered. As a mechanical engineer and then a lab manager at GE Global Research in Niskayuna, New York, he studied how to improve X-ray technology that could one day help doctors diagnose patients sooner and treat them more effectively.

What Frontera didn’t know was that this technology would become critically important to his family. In 2012, his younger son, Adam, then 4 years old, began having vague health problems: stomachaches and unexplained joint pain that gradually became severe. After months of inconclusive visits to his pediatrician, he had trouble walking, eating and sleeping.

Mark and his wife, Tara, insisted that doctors look deeper. They were stunned when Adam was diagnosed with stage 4 high-risk neuroblastoma, a type of cancer that starts in the nervous system and usually occurs in infants or children under age 5.[1]

Before that day, Frontera knew very little about pediatric cancer, which is relatively rare. Researchers suggest that cancer develops differently in children than in adults, and that treatments need to be better customized for children[2] — one reason Frontera and his family now advocate for more resources for kids.

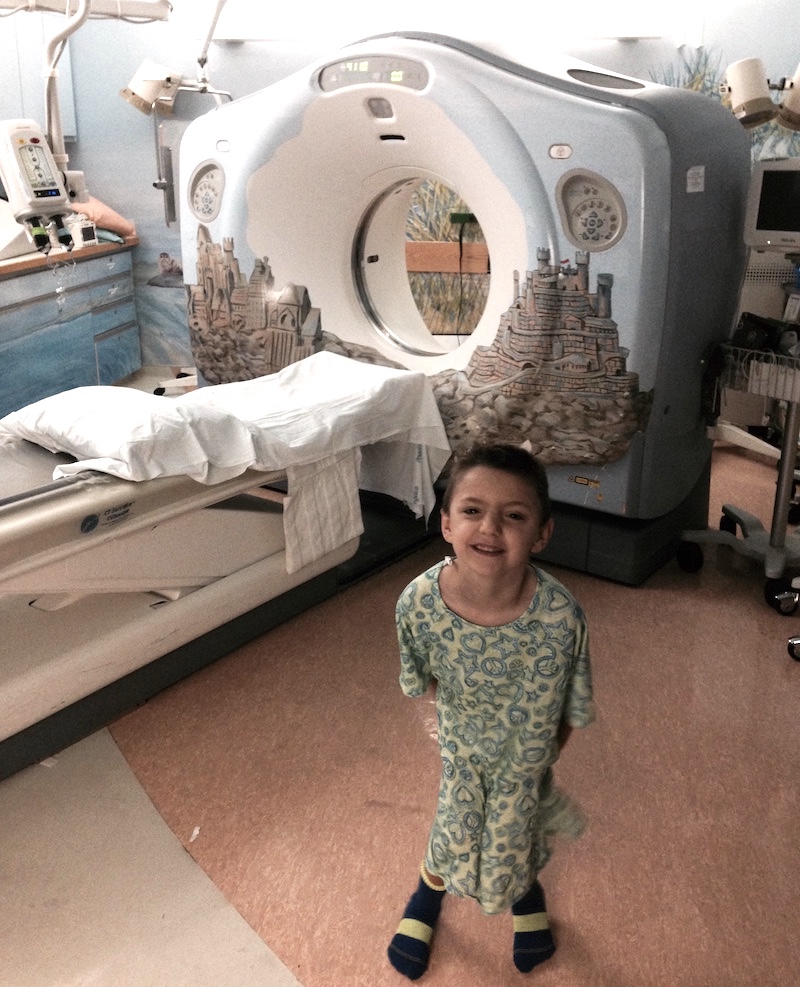

Adam Frontera at the time of his treatment. Top: Mark, Adam, and Tara today.

When Frontera called his GE manager at the time, Gary Strong, to tell him about Adam’s diagnosis, he also thanked him. Strong had been the program manager for the GE Healthcare volumetric computed tomography (VCT) scanner that doctors used to visualize Adam’s tumor, which was located on his adrenal gland. The scanner uses X-rays to produce virtual slices of a patient’s tissue that are pieced together to create a three-dimensional image.

“It was an extremely emotional moment for me,” Frontera recalls. “I told him, ‘Your CT scanner just helped in the staging of Adam’s treatment.’” His son went from initial diagnosis to chemotherapy in less than 48 hours.

So began an aggressive effort to save Adam’s life. The first round of chemotherapy significantly alleviated his pain, but it was only the beginning. During the first year, he spent 189 nights in the hospital.

Adam with his father, Mark Frontera, at the time of his treatment.

“To say Adam’s treatment was horrific is an understatement,” Frontera explains. After chemotherapy came a 12-hour surgery to remove the tumor. Then came more chemotherapy, radioisotope therapy, a stem-cell transplant, radiation therapy, monoclonal-antibody treatment, and retinoic acid treatment — each bringing its own severe side effects.

The family tried to focus on each stage without worrying about the next one. They also tried to make it as fun for Adam as they could, given the circumstances. Volunteer groups brought therapy dogs for comfort. Mark and Tara bribed Adam with gifts. One night, Mark stayed with him in the hospital, and they watched a movie and got candy — a memory his son still talks about.

Frontera deliberately ignored the survival rates for children with neuroblastoma, avoiding anything that might make him lose hope. “There is a whole industry working to improve the odds every day,” he says. “It brought me peace to know that Adam had more tools at his disposal than a kid did six months earlier. The odds have changed dramatically since he went through this 10 years ago — favorably.”

Adam and Mark on the last day of treatment.

Adam contributed to this process by participating in an experimental treatment called MIBG therapy, which uses a highly radioactive drug that directly targets tumor cells. This treatment helped him improve enough to qualify for a stem-cell transplant and provided researchers with more data that can help children in the future.

Mark coped with the fear and uncertainty about Adam’s health in part by striving to make CT scanners better. He was newly grateful for each member of the GE Healthcare team who contributed to the X-ray and other imaging technologies involved in Adam’s care.

“For me, it was a very therapeutic outlet to come home at night and stay up working on an area where you knew you could have a small part in an improvement that, years down the line, will be part of the solution,” he says.

After two years of treatment, Adam was pronounced in remission in 2014. Today, he is 14 years old and doing well. “I think I had a positive attitude through it all, even though it was relatively painful,” he says. “And since I was so young, it was definitely easier for me” than for his parents, he adds.

Adam Frontera today.

Adam has some lasting effects from his cancer-fighting regimen, such as hearing loss from chemotherapy, osteochondromas, elevated cardiac risk, and increased iron levels from numerous blood transfusions, but he no longer needs active treatment or even regular screenings, which his doctors eventually discontinued because the risk of recurrence is so low. He loves acting and singing, and he is pursuing his goal of appearing on Broadway.

September is Childhood Cancer Awareness Month, and Frontera remembers the families of the children who didn’t make it. “We grieved with their parents,” he says. “There’s a lot of survivor’s guilt.” But he also wants more people to know about the kids, like Adam, who are thriving years after their diagnosis. “There is the possibility that kids make it through and they do have normal lives,” he says.

For his part, Frontera has become more directly involved in advancing technologies that diagnose and treat cancer. In 2016, he and his family moved to Waukesha, Wisconsin, so that Frontera could take a role at GE Healthcare. Today he is the engineering program manager of GE Healthcare’s Deep Silicon Project. He leads the development of a next-generation imaging technology that aims to use silicon as a semiconductor for a photon-counting CT detector. Photon-counting CT[3] has the potential to more accurately convert an X-ray photon into an electrical signal, helping doctors see tiny details of organ structures more clearly, while using a lower radiation dose.

“I’m proud to come into this building every day,” Frontera says. He wants to help save other children’s lives, like the engineers before him helped save Adam’s.

“This,” he says, “is what I owe back to the world.”

REFERENCES

[1] Cleveland Clinic, “Neuroblastoma,” last reviewed December 2020, https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/14390-neuroblastoma.

[2] Heidi Ledford, “Genome Studies Unlock Childhood Cancer Clues,” Nature, February 28, 2018, https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-018-02359-6.

[3] Photon-counting technology is technology in development that represents ongoing research-and-development efforts. These technologies are not products and may never become products. Not for sale. Not cleared or approved by the U.S. FDA or any other global regulator for commercial availability.