Katelyn Nye is no stranger to medical devices, and not just because she helps design them for a living. The engineer works on improving X-ray diagnostic equipment, which remains the workhorse imaging technique in hospitals, but years before she became acquainted with medical technology professionally, she experienced it as few others have. One day after a high school basketball practice, she suffered cardiac arrest, the kind we read about striking young athletes now and then. The results are typically fatal, Nye says, but in her case, she survived and then received an implantation of a tiny defibrillator that shocks her heart back into action should it ever stop again.

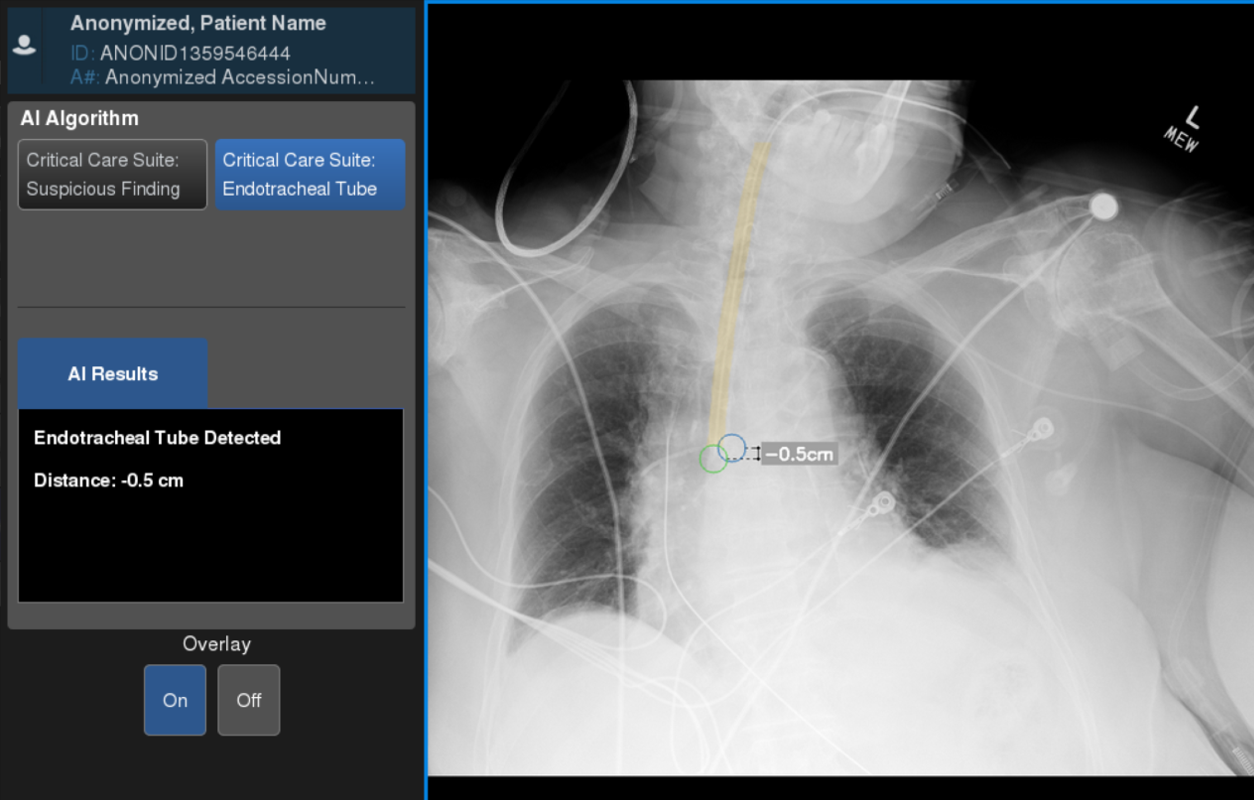

Nye now leads a team at GE Healthcare that recently unveiled a new technology to solve a particularly thorny problem that has long plagued hospitals, but that COVID-19 has made it more urgent. Using artificial intelligence (AI), Nye’s group added an algorithm to mobile X-ray systems that will analyze a patient’s image the moment it’s taken that helps to measure the position of a breathing tube. If that sounds like a mere convenience that will save doctors time and patients a bit of discomfort, consider that as many as a quarter of all patients who are intubated outside of an operating room turn out to have misplaced tubes, which can lead to a host of problems including heart attacks and death.[1][2][3][4][5] Between 5% and 15% of COVID patients require a breathing tube connected to a ventilator, and up to 45% of all ICU patients need a breathing tube, so the numbers and severity of patients aren’t small.[6][7][8][9]

“The concern from the hospitals was really around patient safety as a fast response to critical conditions,” says Nye, who worked with clinical partners to learn what problems AI might help solve. “That's where we really sort of birthed the idea.”

The problem of placing a breathing tube properly isn’t new. Standard hospital procedure is to insert a tube and snap an X-ray immediately after to make sure it’s positioned correctly. For an endotracheal tube, the kind that COVID patients receive, the end of the tube must be placed within a certain distance above the carina, where the windpipe branches into each lung. Most of the time that happens, but when it doesn’t, it can lead to complications, some severe like a collapsed lung.[10]

In an ideal world, a radiologist would read an ICU patient’s X-ray shortly after a tube is placed. In the real world, X-rays form a queue and radiologists work their way down the line. In urgent cases it may take eight hours or more for a radiologist to read an image — and cases not deemed urgent might take even longer to be read.[11] A patient who presents in an ER with mild pain may in fact have a life-threatening condition that an X-ray can reveal, if only someone is available to interpret the data.

The new AI software, developed by the GEHC Edison AI and X-ray AI Engineering teams, automatically analyzes where the tube is placed and displays the measurement results near instantaneously on the same screen as the X-ray image itself, while also sending the data to the radiology team.

AI Viewer misplaced example

“Seconds and minutes matter when dealing with a collapsed lung or assessing endotracheal tube positioning in a critically ill patient,” says Dr. Amit Gupta, Modality Director of Diagnostic Radiography at University Hospital Cleveland Medical Center and Assistant Professor of Radiology at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland.

For Nye, this obscure quality-of-care issue might have been an abstract problem for her to solve on behalf of GE Healthcare’s customers, as she does many others. But this past summer she and her wife welcomed twin boys to the world, both of whom were born slightly premature, with her son Everest not able to eat. Extra tissue prevented him from swallowing, necessitating surgery and an around-the-clock feeding tube snaking through his nose and down his esophagus. In a twist, the X-ray unit the hospital used to measure the tube’s placement was the one developed by Nye’s team – the AMX 240.

Even now, 6-month-old Everest has to navigate his home with the tube placed just so. Yanking on the tube (something a baby can be expected to do) necessitates a trip back to the hospital for replacement and another X-ray, says Nye. At one point, a radiologist sent a message to her son’s care team that his tube was misplaced. But before the team could reposition it, Nye realized the radiologist was reading an X-ray image from hours ago, before the tube had already been replaced.

“I was awoken in the middle of the night in the hospital by a team saying we're going to take his tube and push it down further,” recalls Nye. “I had to say, ‘Stop, stop, stop. That was two tubes ago.’ Innovations like Critical Care Suite, leveraging embedded AI at the bedside for evaluating medical tube and line positions, might prevent these types of medical errors in the future.”

This kind of mix-up due to a delay in reading X-rays is not rare, says Nye, and it can occasionally kill if, say, a feeding tube is inserted into a patient’s windpipe by accident.

The endotracheal tube positioning algorithm is part of a bundle of AI algorithms called Critical Care Suite that GE’s X-ray business is embedding into their latest X-ray machines. Other algorithms ensure the X-ray image is of sufficient quality and help doctors prioritize those that need prompt attention if a pneumothorax (collapsed lung) is detected. Embedding the software directly into the scanner, as opposed to moving images to the cloud for analysis, means results are faster and a potentially life-threatening emergency could be addressed bedside when a clinician is already there.

It would normally take up to two years to bring a product like this to market, says Nye, but GE Healthcare engineers, data scientists and regulatory specialists did it in 12 months, despite the fact that much of the software was developed by teams in India while COVID was rampaging there.

“The country was on house arrest, and they and their families were falling ill with COVID-19 while hospitals were so overwhelmed, access to care was challenging,” says Nye. “Yet the team remained so dedicated to the cause of bringing innovative AI to the world to aid in the fight against the pandemic, and despite the challenges, the project wasn’t slowed down.”

Nye says although X-rays don’t have the same capabilities as more modern techniques like MRI or CT, they remain relatively inexpensive, convenient and easier to produce with less training — and they’ll continue to evolve and improve, thanks to AI. Her own condition has never been resolved nor definitively diagnosed and her heart has needed the implanted defibrillator repeatedly over the years to prevent her from going into cardiac arrest. And her son Everest is gaining weight but will require a feeding tube for some time.

[1] Jemmett ME, Kendal KM, Fourre MW, Burton JH. Unrecognized misplacement of endotracheal tubes in a mixed urban to rural emergency medical services setting. Acad Emerg Med 2003;10:961–5.

[2] Katz SH, Falk JL. Misplaced endotracheal tubes by paramedics in an urban emergency medical services system. Ann Emerg Med 2001;37:32–7.

[3] Lotano R, Gerber D, Aseron C, Santarelli R, Pratter M. Utility of postintubation chest radiographs in the intensive care unit. Crit Care 2000;4:50–3.

[4] McGillicuddy DC, Babineau MR, Fisher J, Ban K, Sanchez LD.

[5] Is a postintubation chest radiograph necessary in the emergency department? Int J Emerg Med 2009;2:247–9.

[6] Möhlenkamp S, Thiele H. “Ventilation of COVID-19 patients in intensive care units.” Nature Public Health Emergency Collection. 2020 Apr 20 :1–3

[7] Hannah Wunsch, Jason Wagner, Maximilian Herlim, David Chong, Andrew Kramer, and Scott D. Halpern. ICU occupancy and mechanical ventilator use in the United States. Crit Care Med. 2013 Dec; 41(12): 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318298a139.

[8] Dawei Wang, Bo Hu, Chang Hu, et al. Clinical Characteristics of 138 Hospitalized Patients With 2019 Novel Coronavirus–Infected Pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323(11):1061-1069. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.1585

[9] Lingzhong Meng, M.D.; Haibo Qiu, M.D.; Li Wan, M.D.; Yuhang Ai, M.D.; Zhanggang Xue, M.D.; et al. Intubation and Ventilation amid the COVID-19 Outbreak: Wuhan’s Experience. Anesthesiology 6 2020, Vol.132, 1317-1332.

[10] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6513417/

[11] Rachh, Pratik et al. “Reducing STAT Portable Chest Radiograph Turnaround Times: A Pilot Study.” Current Problems in Diagnostic Radiology Vol. 47, No. 3 (n.d.): 156–60. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0363018817300312?via=ihub.